FEATURE – We are used to approaching strategic thinking as if our organization was in a position of stability and dominance. What if we started to look at it as creating better deals with all parties involved?

Words: Michael Ballé, Eivind Reke and Daryl Powell

We were sitting in on a very clear strategy presentation at a third-generation business. There were strategic goals, key objectives, battles that must be won, and action plans. It followed the classic strategic framework based on Drucker’s management-by-objectives thinking. To try to deepen our understanding, we discussed what the expected gains were – what benefits the company looked for from these battles and how likely it was to achieve them. As the discussion progressed, however, it became apparent that the key results they needed were in other players’ hands.

Picture a family-owned food company. Some of the key drivers for sales and profit include:

- The weather (because of the nature of their product).

- The distributor.

- The marketing agency that supports the brand.

- The machine manufacturer that agrees (or not) to make more or less flexible and robust machines (important for the food company to cope with huge variation in demand).

- The people needed to work in production.

As we talked it through, it became clear that the “OKRs”, objectives and key results, depended on people and processes over which the company had no control. We started discussing how the current owner’s grandfather had started the business and the various deals he had to make to turn a craftsman’s shop into an industrial operation – some good, some not so good, some terrible (specifically, those with bankers). He would never have thought of strategy as goals, objectives, and so on. He would have thought of it in terms of deals. Not surprisingly, this is exactly how the entrepreneurs we know, who started their own businesses, think. So why were we sitting there listening to a presentation that built on the premises that the company could control its own destiny? To get to that, we need to take a little detour into learning theory, so please bear with us.

Mental models are incredibly sticky. They are the mental maps of the world that we mobilize to understand things, particularly invisible things, such as the future or intangibles like organizations and relationships. Most of what we experience as learning is “single loop” learning: we see the gap between reality and our expected vision of it and try to correct it. In effect, we try to change real life to defend our mental status quo. We have set our minds on a few governing variables related to what we think we want and then react according to events to maintain them as stable as possible.

True learning, however, is “double loop” learning. It comes into play when we realize that, in order to achieve the success our hearts desire, we need to change our governing variables; and it is necessary to turn our entire mental model on its head and start to think and act differently. When we see where our actions are truly leading us in practice versus our goals, we are – rarely – pushed to change our mental models and redefine the governing variables of our actions. These cathartic “a-ha moments” are rare and often difficult to manage, because they entail changing our map of a situation and our understanding of the world. In lean, a typical example is shifting from the governing variable of mass production – maximizing local output through bigger, faster single-product machines – to that of lean production – maximizing flexibility to improve global output through pull and flow. Rather than govern through pushing production, you change to increasing flexibility and quality.

Going back to the presentation we were witnessing, the goals -> objective -> actions model we saw in action implies the company is in a position of dominance – or searching for dominance to assert power. This is the American Porter model of strategy taught in MBAs. It also implies stability. But what if you’re not dominant, and operate in an unstable environment, like the company we visited (which is completely dependent on access to distribution channels and on the weather for its sales)?

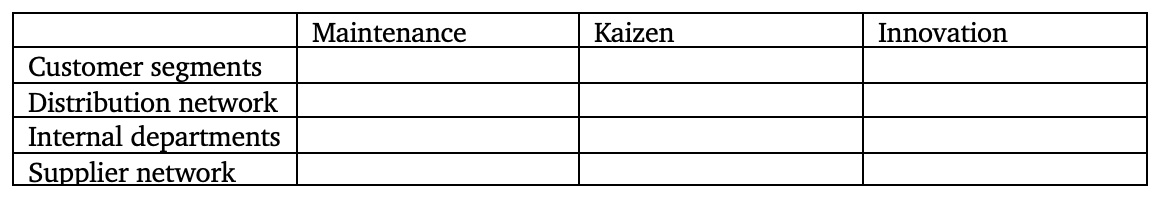

In a context of low dominance and low stability, we can change our mental models and look at strategy as deals with the parties we are completely dependent on. These deals either get better, stay stable, or get worse. In fact, we can look at each deal in Masaaki Imaï’s lean terms:

Looking at each critical deal that sustains our business, we can think in terms of:

- Are we doing the maintenance of the deal?

- What kaizen are we supporting on the deal?

- Are we looking at innovation opportunities?

Continuing this line of thinking, we can adopt the Toyota vision of looking at a value network rather than a supply chain. Supply chain is a construct that implies we are all like Apple. That our organization is in a position of market stability and complete dominance, where every other actor in the supply chain is completely dependent on us. However, this is not the case for most companies. But if we adopt a value network perspective and combine it with Imai, we can envision a framework like this:

This simple framework completely redefines our strategic vision, as well as the key skills we need to develop and succeed. For instance, it brings persuasive communication, negotiation, and conflict management to the forefront of managerial skills – not a surprise when you think about it, but how many executives formally develop their competence in these areas as opposed to calculating, organizing, and controlling (the skills they typically need in a dominant setting)?

Thinking in terms of deals completely changes our outlook on the situations we face. Rather than imagine the ideal future state (for us) and the implementation path to achieve it (regardless of what everybody says), we need to look at things differently:

- What is the mutually agreed space for win-win and the opportunities to explore for mutual gain as well as the lose-lose scenarios we both want to avoid in our current business situation?

- What is the discussion process and how are the invitation of new information and ideas, the organization of physical spaces for discussion (for instance obeyas or reviews), and the facilitation of difficult conversations handled?

- Emotions and egos must be taken as facts that are part of the deal – identity roles (“I’m an IT manager, how do you expect me to know about distribution?”), emotional outbursts and motivational ups and downs are an integral part of the robustness of the deal.

- Nurturing the relationship is just as important as the object of the deal being discussed and involves a clear give and take – in order to achieve this, I have to gladly give that.

Lean practitioners will be familiar with these elements (which are part and parcel to any people-centric approach), but they are rarely looked at explicitly as tools to achieve better results. Thinking in terms of deals means changing our vision from “who does what to get things done” to “who talks to whom to move things forward?”.

Following this through to its logical conclusion, management can be seen as constructively organizing solutions to inherent conflicts between players, which, it turns out, is Herbert Simon and James March’s definition of organizations in the 1950s: “Organizations are systems for coordinated action among individuals and groups whose preferences, information, interests, or knowledge differ. Organization theory describes the delicate conversion of conflict into cooperation, the mobilization of resources, and the coordination of effort that facilitates the join survival of an organization and its members.” (From the 1958 book Organizations)

Once one abandons dominance as a governing variable (who of us is dominant unless you work for a multinational?), we can discover completely new and more effective ways to think about strategy – and indeed, lean strategy – in terms of creating a communication structure that supports kaizen and teaches people to better solve problems collaboratively.

- Is the deal getting better or worse?

- Is the communication structure (such as just-in-time) supporting a better deal?

- Are people trained in collaborative problem solving?

Our minds believe what they understand, this is a feature, not a bug. Something easy to understand is easy to believe, which is why exploring new thinking is so hard. Our minds demand that we return to the old thinking we are comfortable with, no matter how wrong it appears in terms of fit-to-fact. Every small company we know has adopted the strategy of dominant multinationals:

- Set our financial goals.

- Turn them into operational objectives.

- Draw out action plans.

- Make our managers implement those plans.

But this thinking has deep hidden assumptions such as:

- Set our financial goals – we are in complete control of our markets.

- Turn them into operational objectives – we completely know how operations turn into profit.

- Draw out action plans – we know and make all the right decisions.

- Make our managers implement those plans – our managers have the power and skill to implement them.

If these hidden assumptions are spelled out, the splendid sounding strategy doesn’t look so promising after all – most of the time companies are in the situation of low control of markets, little knowledge on how operations turn into profit, make both good and bad decisions, and have managers with low power and medium skills. So, not an encouraging picture.

If we apply Lean Thinking to the strategic framework, we can come up with an alternative view on strategy:

- Look at the people who hold the key to our success (externally and internally).

- Look at the deal we have with them: is it getting better or worse?

- Devise a maintenance/kaizen/ innovation plan for every deal.

- Teach our executives and managers collaborative problem solving to further these plans.

This will allow us to build success on the strategic opportunities that will emerge of humans thinking and seeking opportunities together (as well as overcoming obstacles together) – just as the founder of the food company once did to open a path to success.

He didn’t build the company through action plans, but through deals that allowed him to sell his products, to be supplied raw materials and machines by suppliers and vendors, to have people come and work for him, and to have banks finance his operation. After the deals were made, they were maintained and improved upon, generation after generation. The current owner and CEO is improving and maintaining these deals to ensure the survival of the company so that it can be passed on to the next generation.

We all say lean is a people-centric solution, but when push comes to shove, we all make the mistake of looking at the mechanics of the job by applying standards as rules, or at the mechanics of material flow by applying rules to logistics. But people make deals; they don’t apply rules. People-centric lean means looking at strategy as deals that improve or get worse. Since every deal has conflicts and every person has their needs and wants, we apply PDCA as the core way to improve deals by collaboratively solving problems and use visual management to create the areas to have the conversations that enable us to create those deals and resolve conflict. So, think about it, what hidden assumptions are implicit in your strategic thinking, and what deals are you neglecting to maintain, hesitant to re-negotiate or failing to make?

THE AUTHORS