FEATURE – This article (and video) explains how Michigan Medicine applied lean product and process development tools and methods to their clinical processes. A powerful experiment.

Words: Jim Morgan, Senior Advisor, Lean Product Development at Lean Enterprise Institute

“Let’s run an experiment.” Exactly the response you would expect from a lean healthcare veteran like Dr. Jack Billi (PL profiled him a few months ago). And with that we wrapped up our discussion on lean in healthcare and headed to the gemba at Michigan Medicine (formerly University of Michigan Health Systems). We wanted to see how we might apply lean product and process development (LPPD) principles to a healthcare environment.

One of the first people we met there was UofM Chief Quality Officer, Dr. Steven Bernstein, who directed us to Clinical Design and Innovation (CDI) team led by Dr. Larry Marentette and Paul Paliani. They had already experienced a good deal of success applying lean principles to clinical processes, but were facing new and daunting challenges as both expectations for the team and their workload grew. The CDI team was eager to find a better way to work together and meet these new challenges.

In the video below, taken at Michigan’s Lean Thinkers forum, the CDI team and I share some of their path-breaking work, which started – as it happens in lean organizations – with the CDI team’s willingness to run an experiment. Here are just a few of the highlights.

The CDI team and their Lean Enterprise Institute LPPD coach Matt Zayko started by value stream mapping (VSM) their clinical process development activities. One of the first things highlighted by the product development mapping work revealed that the CDI team’s “head and neck post-surgical process” project ended up taking six months longer than scheduled, and that they accomplished only about half of the original vision for the project. However, the VSM exercise also enabled the team to “see the work”, the issues and the delays so that they could take action. Among the issues that needed tackling, they identified:

- Long delays in acquiring data and scheduling meetings with key stakeholders and process owners early in CDI projects;

- Lack of alignment on goals and objectives for the program with key stakeholders and a tendency to jump into doing work too soon;

- They did not have an effective way of identifying and reacting to issues quickly.

In the future state they agreed to experiment with the following potential LPPD-based countermeasures:

- Operate all programs using a common obeya management system and milestones to improve collaboration, communication, learning and project management effectiveness;

- To frontload their process with a “study period” and increased stakeholder engagement, experimentation and learning;

- Create a concept paper through the work in the study period to better align the team and key stakeholders;

- To incorporate design reviews and targeted prototyping to improve problem solving and increase innovation.

YOU CAN’T MANAGE A SECRET

One of the first things to resonate with the CDI team was Ford’s former CEO Alan Mulally’s philosophy that “you can’t manage a secret”. Schedules and other important information were generally squirreled away on project leaders’ laptops and each improvement pair operated independently. They badly needed greater transparency, increased cross-project learning, and improved collaboration in order to improve project outcomes, decrease lead-time and successfully manage their increased workload.

And to better understand if projects were truly on schedule, the CDI team created quality of event criteria (QEC) for each milestone. They started with a clear purpose statement for each milestone, and derived QEC from that. By measuring their progress against these criteria, they could more easily determine normal from abnormal conditions and react to it accordingly. They also created key indicators for early warning of milestones in jeopardy.

STUDY PERIOD

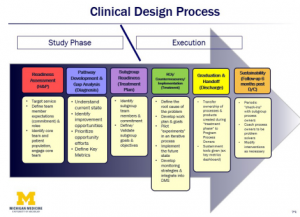

Another problem the team uncovered was that they were sometimes doing too much work on a project before they fully understood the current situation or had key stakeholders on board. To address this issue, they reorganized their Clinical Design Process to include a study phase and an execution phase, consisting of six steps that correlated with medical terminology. The study phase allows the team to focus on achieving a deep understanding of the patient, of the process owner, and of the environment and enables them to experiment to learn. To do this they increased their time at the gemba significantly and began to do more “co-development” with processes owners work up front.

They also began to create their own low-fidelity prototypes that they tested with key stakeholders utilizing their newly-acquired observation skills and methods. Examples of the early, targeted prototypes included pocket cards, patient care outlines, and sketches of software interfaces, and process flows. Rapid experimentation with these prototypes helped them gain better clarity, identify and resolve issues, align with stakeholders and ultimately create more effective tools and technology to enhance clinical processes.

CONCEPT PAPER

The most recent LPPD tool that the CDI team agreed to experiment with was the concept paper: project managers Heidi McCoy and Andy Scott began to create concept papers for their projects based on the work being done during the study period. The aim was to improve their internal logic, create a better project plan, and (critically) align with all key stakeholders. The concept papers have proven to be a powerful communication tool.

DESIGN REVIEWS

Cross-functional design reviews are being held with all supporting groups involved with the each process project. Once they complete a study period and have a good understanding of the problem, key gaps, stakeholders, etc, they organize into appropriate subgroups, each focused on a specific element of the new clinical process.

The Clinical Design program used two types of design reviews:

- An innovation design review that happens within each subgroup team on a biweekly cadence – it includes all members of the subgroup. They work on root-cause analysis, develop countermeasures, create low-fidelity prototypes, and experiment.

- Integration design reviews to look at how all the subgroups align and integrate their work, as well as the process launch.

It is early days in the CDI team’s LPPD journey. However, they have done a remarkable job and already experienced some significant benefits from applying these principle and methods to their work. Cross-team collaboration and learning have increased, and the team can now cover far more information in their 30-minute obeya stand-up meetings than they ever did in their previous one-hour status meetings. They have spent more time at the gemba, being much more effective at engaging stakeholders, and better understood projects in the early days of their projects by working though a study period, and then communicated that understanding through the concept papers. The design reviews have surfaced and resolved issues proactively and generated far more innovation and collaboration.

I believe that this work has the potential to significantly improve patient outcomes and change the way healthcare processes are created in the future – and it all started because the team had the courage to run an experiment.

*This story draws extensively from the upcoming book “Designing the Future” by James Morgan and Jeffery Liker, McGraw Hill – Lean Enterprise Institute, 2018*

Join Jim and many others at the inaugural Lean Product and Process Development conference “Designing the Future”

Traverse City, Michigan – June 19-20

THE AUTHOR

Jim Morgan is Senior Advisor for lean product development at the Lean Enterprise Institute. A long-time researcher and leader in the field, he was Director, Global Body Exterior, Safety, and SBU Engineering at Ford Motor Company during the product-led revitalization under CEO Alan Mulally. Prior to joining Ford, he was Vice President at TDM, a tier one, global automotive supplier of engineering services, prototypes, tools, and low volume parts and assemblies. Jim holds a PhD in Engineering from the University of Michigan. He is co-author of The Toyota Product Development System based on his award winning research. Contact Jim atjmorgan@lean.org